At This Point We Leave Africa

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/migrations_jul08_631.jpg)

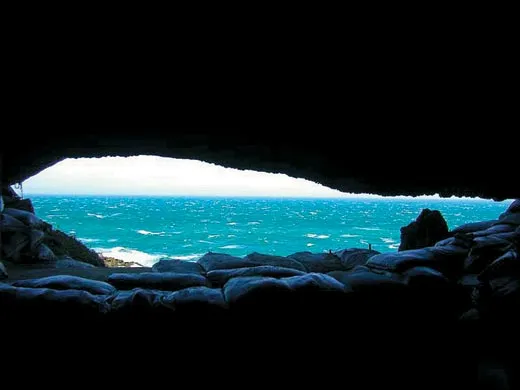

Seventy-seven thousand years ago, a craftsman sat in a cavern in a limestone cliff overlooking the rocky coast of what is at present the Indian Bounding main. It was a beautiful spot, a workshop with a glorious natural moving-picture show window, cooled by a sea cakewalk in summer, warmed by a minor fire in wintertime. The sandy cliff acme to a higher place was covered with a white-flowering shrub that 1 afar day would be known as blombos and give this place the name Blombos Cavern.

The man picked up a slice of reddish chocolate-brown rock most three inches long that he—or she, no 1 knows—had polished. With a rock indicate, he etched a geometric blueprint in the flat surface—unproblematic crosshatchings framed past two parallel lines with a third line down the centre.

Today the stone offers no clue to its original purpose. Information technology could accept been a religious object, an decoration or just an aboriginal putter. Just to encounter it is to immediately recognize it equally something just a person could have made. Carving the rock was a very homo thing to exercise.

The scratchings on this piece of ruddy ocher mudstone are the oldest known example of an intricate design made by a human beingness. The ability to create and communicate using such symbols, says Christopher Henshilwood, leader of the team that discovered the stone, is "an unambiguous marker" of modern humans, one of the characteristics that divide us from any other species, living or extinct.

Henshilwood, an archaeologist at Norway'due south University of Bergen and the University of the Witwatersrand, in South Africa, found the carving on land owned by his grandfather, nigh the southern tip of the African continent. Over the years, he had identified and excavated nine sites on the property, none more than half dozen,500 years old, and was not at kickoff interested in this cliffside cave a few miles from the South African boondocks of Nonetheless Bay. What he would find at that place, however, would change the mode scientists think about the evolution of mod humans and the factors that triggered mayhap the most important event in human prehistory, when Homo sapiens left their African homeland to colonize the world.

This swell migration brought our species to a position of earth potency that it has never relinquished and signaled the extinction of whatever competitors remained—Neanderthals in Europe and Asia, some scattered pockets of Homo erectus in the Far East and, if scholars ultimately decide they are in fact a separate species, some diminutive people from the Indonesian island of Flores (see "Were 'Hobbits' Human?"). When the migration was complete, Man sapiens was the last—and only—homo continuing.

Even today researchers argue well-nigh what separates mod humans from other, extinct hominids. More often than not speaking, moderns tend to be a slimmer, taller breed: "gracile," in scientific parlance, rather than "robust," similar the heavy-boned Neanderthals, their contemporaries for mayhap 15,000 years in ice age Eurasia. The mod and Neanderthal brains were nearly the same size, only their skulls were shaped differently: the newcomers' skulls were flatter in back than the Neanderthals', and they had prominent jaws and a straight forehead without heavy forehead ridges. Lighter bodies may have meant that modern humans needed less food, giving them a competitive advantage during hard times.

The moderns' behaviors were also different. Neanderthals made tools, but they worked with chunky flakes struck from large stones. Modern humans' stone tools and weapons unremarkably featured elongated, standardized, finely crafted blades. Both species hunted and killed the aforementioned large mammals, including deer, horses, bison and wild cattle. But moderns' sophisticated weaponry, such as throwing spears with a diverseness of carefully wrought rock, bone and antler tips, made them more successful. And the tools may have kept them relatively safe; fossil evidence shows Neanderthals suffered grievous injuries, such equally gorings and bone breaks, probably from hunting at close quarters with short, rock-tipped pikes and stabbing spears. Both species had rituals—Neanderthals buried their dead—and both made ornaments and jewelry. Merely the moderns produced their artifacts with a frequency and expertise that Neanderthals never matched. And Neanderthals, as far every bit we know, had nothing like the etching at Blombos Cave, let alone the bone carvings, ivory flutes and, ultimately, the mesmerizing cave paintings and stone art that modernistic humans left every bit snapshots of their globe.

When the study of man origins intensified in the 20th century, two main theories emerged to explain the archaeological and fossil record: 1, known every bit the multi-regional hypothesis, suggested that a species of human antecedent dispersed throughout the earth, and modern humans evolved from this predecessor in several different locations. The other, out-of-Africa theory, held that modern humans evolved in Africa for many thousands of years earlier they spread throughout the rest of the world.

In the 1980s, new tools completely changed the kinds of questions that scientists could respond about the past. By analyzing Deoxyribonucleic acid in living man populations, geneticists could trace lineages backward in time. These analyses accept provided key support for the out-of-Africa theory. Homo sapiens, this new evidence has repeatedly shown, evolved in Africa, probably around 200,000 years ago.

The first DNA studies of human development didn't use the Dna in a jail cell'due south nucleus—chromosomes inherited from both male parent and mother—but a shorter strand of DNA contained in the mitochondria, which are free energy-producing structures inside most cells. Mitochondrial Deoxyribonucleic acid is inherited only from the female parent. Conveniently for scientists, mitochondrial DNA has a relatively loftier mutation rate, and mutations are carried forth in subsequent generations. By comparing mutations in mitochondrial Dna amongst today's populations, and making assumptions about how frequently they occurred, scientists can walk the genetic code astern through generations, combining lineages in ever larger, earlier branches until they reach the evolutionary trunk.

At that point in human history, which scientists have calculated to be about 200,000 years agone, a adult female existed whose mitochondrial Dna was the source of the mitochondrial DNA in every person alive today. That is, all of us are her descendants. Scientists call her "Eve." This is something of a misnomer, for Eve was neither the first modernistic man nor the only woman alive 200,000 years ago. Only she did live at a fourth dimension when the modern homo population was pocket-size—about x,000 people, according to 1 estimate. She is the but woman from that time to accept an unbroken lineage of daughters, though she is neither our only ancestor nor our oldest antecedent. She is, instead, but our "most recent mutual ancestor," at least when it comes to mitochondria. And Eve, mitochondrial Dna backtracking showed, lived in Africa.

Subsequent, more sophisticated analyses using DNA from the nucleus of cells have confirmed these findings, most recently in a report this twelvemonth comparison nuclear DNA from 938 people from 51 parts of the globe. This inquiry, the most comprehensive to date, traced our common ancestor to Africa and clarified the ancestries of several populations in Europe and the Center Due east.

While Dna studies have revolutionized the field of paleoanthropology, the story "is not every bit straightforward every bit people remember," says Academy of Pennsylvania geneticist Sarah A. Tishkoff. If the rates of mutation, which are largely inferred, are non accurate, the migration timetable could be off by thousands of years.

To piece together humankind'southward great migration, scientists blend Deoxyribonucleic acid analysis with archaeological and fossil evidence to endeavor to create a coherent whole—no easy job. A disproportionate number of artifacts and fossils are from Europe—where researchers have been finding sites for well over 100 years—but there are huge gaps elsewhere. "Outside the Near East in that location is almost nix from Asia, peradventure ten dots you could put on a map," says Texas A&M University anthropologist Ted Goebel.

As the gaps are filled, the story is likely to change, but in broad outline, today's scientists believe that from their beginnings in Africa, the modern humans went outset to Asia between 80,000 and 60,000 years ago. Past 45,000 years ago, or possibly earlier, they had settled Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Commonwealth of australia. The moderns entered Europe around xl,000 years ago, probably via two routes: from Turkey forth the Danube corridor into eastern Europe, and along the Mediterranean coast. By 35,000 years ago, they were firmly established in about of the Old World. The Neanderthals, forced into mountain strongholds in Republic of croatia, the Iberian Peninsula, the Crimea and elsewhere, would become extinct 25,000 years ago. Finally, around 15,000 years ago, humans crossed from Asia to North America and from there to South America.

Africa is relatively rich in the fossils of human ancestors who lived millions of years agone (encounter timeline, reverse). Lush, tropical lake country at the dawn of human evolution provided one congenial living habitat for such hominids equally Australopithecus afarensis. Many such places are dry today, which makes for a congenial exploration habitat for paleontologists. Wind erosion exposes quondam bones that were covered in muck millions of years ago. Remains of early on Homo sapiens, by dissimilarity, are rare, not simply in Africa, but also in Europe. One suspicion is that the early moderns on both continents did not—in contrast to Neanderthals—bury their dead, only either cremated them or left them to decompose in the open.

In 2003, a team of anthropologists reported the discovery of three unusual skulls—ii adults and a kid—at Herto, near the site of an aboriginal freshwater lake in northeast Federal democratic republic of ethiopia. The skulls were between 154,000 and 160,000 years onetime and had mod characteristics, but with some primitive features. "Fifty-fifty now I'm a lilliputian hesitant to call them anatomically modern," says squad leader Tim White, from the Academy of California at Berkeley. "These are large, robust people, who haven't quite evolved into modern humans. Nevertheless they are so close you lot wouldn't desire to give them a unlike species proper name."

The Herto skulls fit with the DNA analysis suggesting that modern humans evolved some 200,000 years agone. But they too raised questions. There were no other skeletal remains at the site (although there was bear witness of butchered hippopotamuses), and all three skulls, which were most consummate except for jawbones, showed cut marks—signs of scraping with stone tools. It appeared that the skulls had been deliberately detached from their skeletons and defleshed. In fact, part of the child's skull was highly polished. "It is hard to argue that this is not some kind of mortuary ritual," White says.

Fifty-fifty more provocative were discoveries reported terminal yr. In a cave at Pinnacle Betoken in South Africa, a squad led by Arizona State University paleoanthropologist Curtis Marean constitute evidence that humans 164,000 years agone were eating shellfish, making complex tools and using ruby ocher pigment—all modern human behaviors. The shellfish remains—of mussels, periwinkles, barnacles and other mollusks—indicated that humans were exploiting the sea as a food source at least 40,000 years earlier than previously thought.

The get-go archaeological bear witness of a human migration out of Africa was plant in the caves of Qafzeh and Skhul, in present-mean solar day Israel. These sites, initially discovered in the 1930s, contained the remains of at least 11 mod humans. Most appeared to accept been ritually buried. Artifacts at the site, however, were uncomplicated: hand axes and other Neanderthal-style tools.

At outset, the skeletons were thought to be 50,000 years old—modern humans who had settled in the Levant on their way to Europe. Only in 1989, new dating techniques showed them to be 90,000 to 100,000 years old, the oldest modernistic human remains always establish exterior Africa. Simply this excursion appears to be a dead cease: there is no testify that these moderns survived for long, much less went on to colonize any other parts of the earth. They are therefore non considered to exist a function of the migration that followed 10,000 or 20,000 years afterward.

Intriguingly, 70,000-year-old Neanderthal remains have been found in the aforementioned region. The moderns, it would appear, arrived first, only to move on, dice off because of disease or natural ending or—possibly—go wiped out. If they shared territory with Neanderthals, the more than "robust" species may have outcompeted them hither. "You may be anatomically modernistic and display modern behaviors," says paleoanthropologist Nicholas J. Conard of Germany'due south University of Tübingen, "only apparently it wasn't enough. At that betoken the 2 species are on pretty equal footing." Information technology was besides at this point in history, scientists concluded, that the Africans ceded Asia to the Neanderthals.

Then, about 80,000 years agone, says Blombos archaeologist Henshilwood, modern humans entered a "dynamic menses" of innovation. The evidence comes from such South African cave sites as Blombos, Klasies River, Diepkloof and Sibudu. In addition to the ocher carving, the Blombos Cave yielded perforated ornamental beat chaplet—amidst the earth's get-go known jewelry. Pieces of inscribed ostrich eggshell turned upward at Diepkloof. Hafted points at Sibudu and elsewhere hint that the moderns of southern Africa used throwing spears and arrows. Fine-grained stone needed for careful workmanship had been transported from up to 18 miles abroad, which suggests they had some sort of trade. Bones at several South African sites showed that humans were killing eland, springbok and fifty-fifty seals. At Klasies River, traces of burned vegetation suggest that the ancient hunter-gatherers may take figured out that past clearing land, they could encourage quicker growth of edible roots and tubers. The sophisticated bone tool and stoneworking technologies at these sites were all from roughly the same time menses—betwixt 75,000 and 55,000 years ago.

Virtually all of these sites had piles of seashells. Together with the much older show from the cavern at Top Point, the shells suggest that seafood may take served as a nutritional trigger at a crucial indicate in human history, providing the fatty acids that modern humans needed to fuel their outsize brains: "This is the evolutionary driving strength," says University of Cape Town archaeologist John Parkington. "It is sucking people into beingness more cognitively enlightened, faster-wired, faster-brained, smarter." Stanford University paleoanthropologist Richard Klein has long argued that a genetic mutation at roughly this point in human history provoked a sudden increase in brainpower, perhaps linked to the onset of speech.

Did new engineering science, improved nutrition or some genetic mutation allow modern humans to explore the world? Peradventure, only other scholars indicate to more than mundane factors that may accept contributed to the exodus from Africa. A recent Dna study suggests that massive droughts before the great migration split Africa'southward mod man population into small, isolated groups and may have even threatened their extinction. Merely subsequently the weather improved were the survivors able to reunite, multiply and, in the end, emigrate. Improvements in technology may have helped some of them set out for new territory. Or common cold snaps may have lowered sea level and opened new land bridges.

Whatsoever the reason, the ancient Africans reached a watershed. They were set to leave, and they did.

DNA evidence suggests the original exodus involved anywhere from 1,000 to 50,000 people. Scientists do not concur on the time of the departure—sometime more recently than eighty,000 years ago—or the deviation point, only most now appear to exist leaning away from the Sinai, once the favored location, and toward a state bridge crossing what today is the Bab el Mandeb Strait separating Djibouti from the Arabian Peninsula at the southern end of the Red Sea. From in that location, the thinking goes, migrants could have followed a southern route due east forth the coast of the Indian Body of water. "Information technology could take been almost adventitious," Henshilwood says, a path of least resistance that did not require adaptations to different climates, topographies or nutrition. The migrants' path never veered far from the bounding main, departed from warm weather condition or failed to provide familiar food, such as shellfish and tropical fruit.

Tools found at Jwalapuram, a 74,000-year-onetime site in southern Bharat, friction match those used in Africa from the same period. Anthropologist Michael Petraglia of the Academy of Cambridge, who led the dig, says that although no human fossils accept been institute to confirm the presence of mod humans at Jwalapuram, the tools suggest information technology is the earliest known settlement of modern humans exterior of Africa except for the dead enders at Israel'southward Qafzeh and Skhul sites.

And that's about all the physical evidence there is for tracking the migrants' early progress across Asia. To the south, the fossil and archaeological record is clearer and shows that modern humans reached Australia and Papua New Guinea—then part of the same landmass—at least 45,000 years ago, and maybe much earlier.

But curiously, the early downwardly under colonists apparently did not make sophisticated tools, relying instead on simple Neanderthal-style flaked stones and scrapers. They had few ornaments and piddling long-distance merchandise, and left scant evidence that they hunted large marsupial mammals in their new homeland. Of grade, they may have used sophisticated wood or bamboo tools that accept rust-covered. But University of Utah anthropologist James F. O'Connell offers another explanation: the early settlers did not carp with sophisticated technologies because they did not need them. That these people were "modern" and innovative is clear: getting to New Republic of guinea-Australia from the mainland required at to the lowest degree one body of water voyage of more than than 45 miles, an phenomenal achievement. But once in place, the colonists faced few pressures to innovate or adapt new technologies. In particular, O'Connell notes, there were few people, no shortage of food and no need to compete with an indigenous population like Europe's Neanderthals.

Mod humans eventually made their beginning forays into Europe but nearly forty,000 years ago, presumably delayed by relatively common cold and inhospitable weather condition and a less than welcoming Neanderthal population. The conquest of the continent—if that is what it was—is thought to accept lasted most 15,000 years, every bit the last pockets of Neanderthals dwindled to extinction. The European penetration is widely regarded as the decisive event of the groovy migration, eliminating equally it did our last rivals and enabling the moderns to survive at that place uncontested.

Did mod humans wipe out the contest, absorb them through interbreeding, outthink them or simply stand by while climate, dwindling resources, an epidemic or some other natural phenomenon did the job? Perhaps all of the in a higher place. Archaeologists have found footling straight show of confrontation between the two peoples. Skeletal evidence of possible interbreeding is sparse, contentious and inconclusive. And while interbreeding may well accept taken identify, recent DNA studies have failed to evidence any consistent genetic relationship between mod humans and Neanderthals.

"You are always looking for a groovy respond, but my feeling is that you should employ your imagination," says Harvard Academy archaeologist Ofer Bar-Yosef. "At that place may have been positive interaction with the diffusion of technology from one group to the other. Or the modern humans could have killed off the Neanderthals. Or the Neanderthals could accept just died out. Instead of subscribing to one hypothesis or two, I see a composite."

Modern humans' next conquest was the New Globe, which they reached by the Bering Country Bridge—or perhaps past gunkhole—at to the lowest degree 15,000 years ago. Some of the oldest unambiguous prove of humans in the New World is human DNA extracted from coprolites—fossilized feces—plant in Oregon and recently carbon dated to 14,300 years ago.

For many years paleontologists still had one gap in their story of how humans conquered the globe. They had no man fossils from sub-Saharan Africa from between fifteen,000 and 70,000 years ago. Considering the epoch of the corking migration was a blank slate, they could not say for certain that the modern humans who invaded Europe were functionally identical to those who stayed behind in Africa. But one 24-hour interval in 1999, anthropologist Alan Morris of South Africa'due south University of Cape Town showed Frederick Grine, a visiting colleague from Stony Brook University, an unusual-looking skull on his bookcase. Morris told Grine that the skull had been discovered in the 1950s at Hofmeyr, in S Africa. No other bones had been constitute near information technology, and its original resting place had been befouled by river sediment. Whatever archaeological bear witness from the site had been destroyed—the skull was a seemingly useless artifact.

But Grine noticed that the braincase was filled with a carbonate sand matrix. Using a technique unavailable in the 1950s, Grine, Morris and an Oxford University-led squad of analysts measured radioactive particles in the matrix. The skull, they learned, was 36,000 years old. Comparing it with skulls from Neanderthals, early modern Europeans and contemporary humans, they discovered it had nothing in common with Neanderthal skulls and only peripheral similarities with any of today'south populations. But it matched the early Europeans elegantly. The evidence was articulate. 30-vi thousand years agone, says Morris, before the world's human population differentiated into the mishmash of races and ethnicities that exist today, "Nosotros were all Africans."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-human-migration-13561/

0 Response to "At This Point We Leave Africa"

Post a Comment